A few weeks ago, as Jessica McKie was sewing the hem of a pastel velour slip in upstate New York, an Instagram message popped up that made her drop her needle.

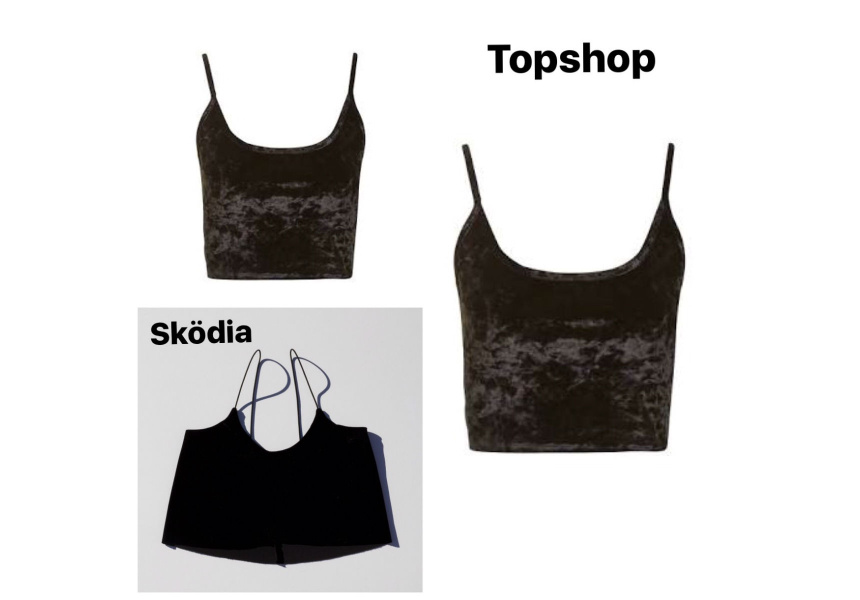

“I saw a photo of someone wearing one of our pink, crushed-velour pieces, and realised it wasn’t ours,” says McKie, the co-founder of New York-based Australian label Sködia. It wasn’t long before she found several replicas online, which she traced back to Topshop.“I looked at their website and it all came together. It was just too damn obvious,” McKie says.

Never miss a Sydney moment. Make sure you're subscribed to our newsletter today.

SUBSCRIBE NOWMcKie alleges that in October last year a junior buyer from Topshop emailed Sködia asking to stock its new collection. “We entertained the idea and sent over our spring/summer ‘17 information, illustrations and lookbook, as requested, which the public was yet to see,” McKie says. Her reply to Topshop was met with silence.

Then earlier this year Topshop released a number of products that looked to McKie very similar to those she had sent the company’s buyer over email. On Topshop’s online store the pieces were being sold for a fraction of the price she had intended to sell them for.

“We’ve had designers copy our work in the past, but this hit a little too close to home,” says McKie. “They had put out numerous styles and exact fabrications … This is extremely disheartening as a smaller designer. Most people know this is something that happens in the fast-fashion industry, but that does not make it okay.”

The copied piece that upset the designer most? The pink, textured-velour slip dress. McKie acknowledges that ’90’s-inspired slips are a big trend at the moment, but regarding Topshop’s pieces she says, “They almost exactly replicated the silhouettes of our sweatpants, tank, slip dresses and tank dress.”

The young designer turned to Instagram for support.

Last week Broadsheet spoke to Topshop’s PR over email. The company’s representative told us the international team declined to respond to Sködia’s allegations. Since that conversation all pieces disputed by Sködia have disappeared from Topshop’s online store and can only be bought on eBay. When asked on Monday why the clothing had been removed from its website, Topshop’s spokesperson said the company did not wish to comment.

The shareability social media has brought to the fashion industry has both improved and worsened the copycat climate.

Alex Farrar, a senior associate at Shiff & Co Lawyers, often deals with similar cases. She says social media is only helpful to a certain extent. “Instagram and other social media sites can be great for naming and shaming commercial enterprises that profit off the creativity of young creatives. But it doesn’t necessarily result in dollars for the designer,” says Farrar.

There have been many other instances of smaller business having products or designs copied by a larger brand. In August last year Gorman was accused of copying the work of Sydney-based fabric designer Eloise Rapp. Wendy Brandes’s jewellery designs were also allegedly “borrowed” in 2012 by Topshop. Even bigger labels aren’t impervious – Topshop also appears to have produced a very similar version of Rihanna’s Puma x Fenti slides.

“It baffles me that these fast-fashion labels can’t gather the resources to come up with their own designs and build a solid team,” says McKie.

Are current copyright laws in Australia protecting young, independent brands such as Sködia? Not unless they have the resources to engage lawyers.

“The purpose [of copyright laws] is to protect the commercial interests of copyright holders. Unfortunately, in order to effectively access [protection by the laws], most people would need to use a lawyer. That’s the big barrier for small designers,” says Farrar.

Another option is registering your design via the Designs Act. “The costs of the registration itself is about $250–$350 per item, but usually involves the work of a lawyer at an additional cost, and it adds up,” says Farrar. “Often designers are left making decisions about which items are the most worthy of being registered.” Because of the cost, Farrar says, “The reality is small designers mostly don’t register anything and it slips through the cracks.”

But in fashion, even registering a design is no guarantee of protection, as fabrication (other than prints) is not protected, and the "strappy tube-dress" design may not be seen to be otherwise distinctive.

So what does this mean for Sködia now? “If the designer shared illustrations with Topshop and Topshop then copied – or substantially copied – those illustrations, that could be a breach of Skodia’s copyright and could be actionable, even if the dress isn’t registered as a design,” says Farrer.

McKie hasn’t decided yet how she’ll proceed. “We are currently working on what avenue will best suit our situation,” she says. “Somebody like us would barely stand a chance, based on funding and the ability to attain the best lawyers,” she says. “This is why they usually get away with [it].”

McKie will instead look into Dianne Von Furstenberg’s Fashion Law Institute program, which supplies free legal advice for people in these situations.

“We are definitely going to be more careful in the future about pre-releasing our lookbooks to anybody, aside from the clients and stockists we trust,” says McKie.