Looming over Redfern, just a short walk from some of Sydney’s hippest bars, you’ll find the Poets Corner flats. Built in 1965 as a response to a severe housing shortage, they might have seen better days but they are still standing.

The inner-city suburb has changed significantly in the more than 50 years since the apartments were constructed. And as redevelopment alters the neighbourhood, the flats’ residents – some of whom have been there for decades – are at risk of being chucked out.

It was the precariousness of the residents’ plight that first inspired Sydney filmmaker Ben Ferris to act. “I cycled to and from work through the housing estates in Redfern and Waterloo for over 10 years,” he says. “Over time the gentrification became significant; it was irreversibly changed.”

Never miss a Melbourne moment. Make sure you're subscribed to our newsletter today.

SUBSCRIBE NOWI catch Ferris between classes at Redfern’s Sydney Film School, which he co-founded, and where he continues to teach writing and directing. He had an instinct, he says, to preserve what he saw. His film 57 Lawson (the address of the flats), shot over two years from 2014 to 2016, is a portrait of the building.

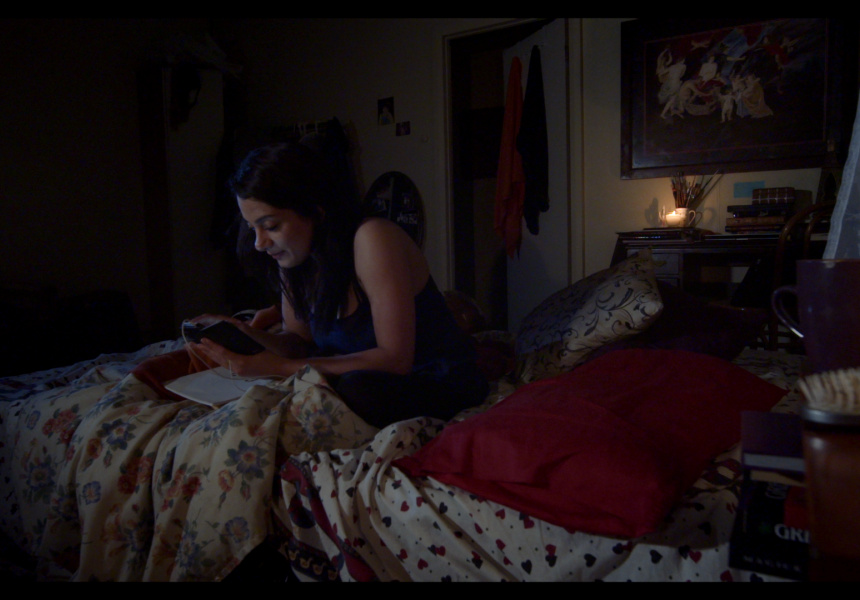

The film (which made its debut at the Sydney Underground Film Festival) is not a documentary in the usual sense – there’s no narration, no attempt to educate – just a slow series of static shots of the building and the people who live there. A door slowly drifts shut for several minutes. We eavesdrop on an ordinary family conversation about a woman being hospitalised for an operation. An old Italian woman narrates her evening, reading through a cake recipe and complaining about the cramped apartment.

Across an hour and a half it slowly builds up an image and a feeling of the place. Ferris doesn’t highlight anything spectacular about the flats but instead shows it as thoroughly ordinary, in the best sense. He wants to show it as it really is for those who live there and in a sense it becomes a moving time capsule.

“My instinct was one of preservation,” says Ferris. “Age, mobility, health, both physical and mental are all factors. A lot of tenants there aren’t in their bloom of youth. Changes to their living situation can be cataclysmic.”

When he first approached residents in 2014 with the idea for the film he was met with skepticism. “There’d been some tabloid programs in which the area hadn’t come off in the best light,” he says. “A lot of social problems were getting foregrounded. But that was precisely the thing I was trying to work against.”

In the wake of the sad fate of the Sirius building in The Rocks, and the Grenfell disaster in London, there’s renewed attention on public-housing residents being at the whims of the property market, with councils and governments following the money.

“There was a strange sense while we were making the film that it was already becoming nostalgic,” says Ferris. “We were watching back footage we’d just shot and it felt like we were digging up material from 20 years ago.”

In the film, council workers meet with frustrated residents to discuss their impeding relocation. “The government has made a decision and now we have to work together,” they say to the residents who neither welcome nor fully understand the news.

That scene is staged – a lone bit of fiction planted in the middle of the stark reality. The residents hadn’t (and still haven’t) been kicked out. One suburb over in Waterloo, social-housing residents are on notice to relocate, with development on the cards. Some residents, though perhaps not all, will be allowed to move back to the area when work is complete. For now, Poets Corner flats is safe but Ferris thinks it’s only a matter of time.

Ferris describes the film’s slowness as a deliberate push against the pace of change. “It comes back to the idea of preservation,” he says. “It’s the antidote to hyper-development, change and destruction.

“It’s an act of defiance.”

57 Lawson is screening at ACMI Cinema 1 on October 27.